The Brazilian capital is a case study in urban planning, full of triumphs and shortcomings

There are few cities in the world that fascinate architecture lovers as much as Brasília, the Brazilian capital built from nothing over an impressively short five-year span in the mid-20th century. When it was inaugurated in 1960, it was unlike any other city in the world, with a radical, artistic urban plan by Lúcio Costa, striking edifices by Oscar Niemeyer, and its avant-garde landscape design by Roberto Burle Marx. “At this time, Brasília was seen as a modern utopia that expressed optimism and trust in the future,” says Dr. Steffen Lehmann, director of the University of Las Vegas’ School of Architecture and the former UNESCO Chair for Sustainable Urban Development. Its bold monumentality demonstrated how Brazil wanted to be perceived by the world: a progressive power. Sixty years later, the metropolis is still lauded as one of the most impressive projects of the 20th century, but perhaps only in the history books. In practice, Brasília has struggled to maintain its original identity as a city of the future.

Despite being a 20th-century city, Brasília’s roots date back to 1789, when revolutionary Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, also known as Tiradentes, first proposed the idea of moving the capital from coastal Rio de Janeiro to a centralized location in the interior of the country. The notion was entered into Brazil’s constitution in 1891, but the plan was not carried out until 1956, under President Juscelino Kubitschek.

By the mid-20th century, the idea of a planned community was somewhat common in a number of countries across the world—the United States, for instance, which, as a relatively young nation, laid quite a bit of groundwork for the concept. Its own capital city, Washington D.C., had the benefit of being planned from scratch at the turn of the 19th century, as did the Australian capital of Canberra, which followed a century later. But Costa had a unique vision for the layout of the city that diverged from the grand axial plans of Washington and Canberra, which he submitted to Kubitschek’s public contest to design the new capital. Dubbed the Plano Piloto, or Pilot Plan, it would take a curvaceous crossed form that many have likened to a plane or a flying bird, a symbol of progress. It would have a centralized hub for a series of monumental government structures—the Square of Three Powers—as well as residential blocks and green space, all designed around a system of highways. After all, a car-based society was the future. Kubitschek selected Costa’s vision as the winner, and the architect enlisted the help of his good friend Niemeyer, with whom he designed Brazilian pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, to create the structures that would fill it.

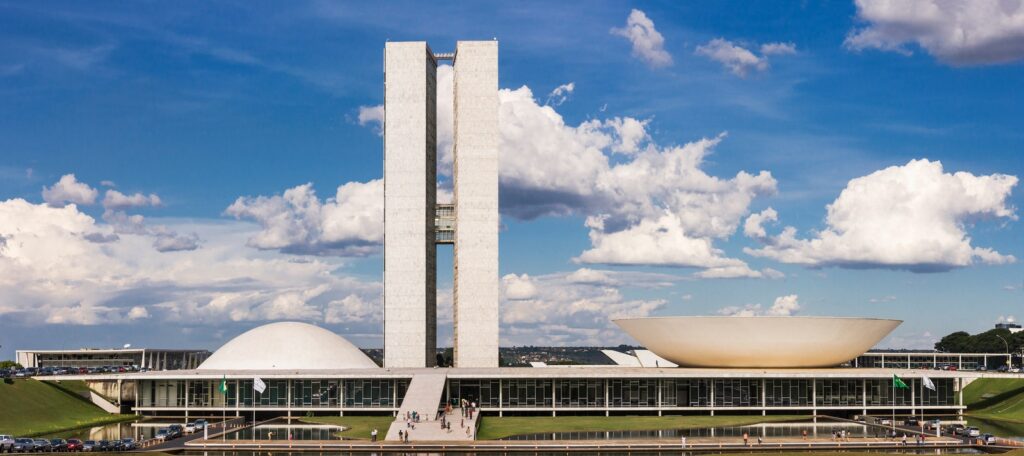

Niemeyer was a visionary of the Brazilian modernist movement, drawing inspiration from Le Corbusier, and he brought a firm sense of futurism to Brasília with stark white structures with sculptural silhouettes: the crown-like Cathedral of Brasília would become one of his most iconic works. While the rest of the world saw these structures as visionary, they were part of the zeitgeist of midcentury Brazil. “We must remember, nowhere else was modernist architecture so enthusiastically embraced and adopted as a national style as in Brazil in the 1940s and ’50s,” says Dr. Lehmann.

Despite Brasília’s reputation as a modernist icon, some critics question the city’s adherence to modernist principles. “In some ways, it was a disappointment in terms of development and the modern movement, because the plan relates much more to Classicism or Neoclassicism or Baroque with the isolated monument to the government center,” says Brian Carter, a professor of architecture at the University of Buffalo. “That is seen as being something which is very different from the aspirations of the modern movement, which was more egalitarian.”

Modernist philosophy aside, the largest critical issue with the Brasília is the very same infrastructure that made it so pioneering. “The original ambition to create a progressive city that would guarantee a good quality of life to all its residents has not totally come to fruition,” says Miami-based architect Kobi Karp. “A good example of that is how the city lacks the typical street life of other traditional Brazilian cities. The majority of people travel in for work and leave to go home at night, not many live and play in the Pilot Plan area.” While the concept of a car-centric city was exciting and novel in the midcentury, global society has since grown to value mixed-use urban plans that have compact, walkable areas. In this sense, Brasília’s plan is far too rigid, a problem exacerbated by its status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which limits redevelopment, despite the city’s significant population growth.

“Brasília is now the fourth-largest city in the country and the home to more than 2.5 million people, yet fewer than 10 percent are residents of the Pilot Plan area. The others live outside in the suburban sprawl,” says Dr. Lehmann. “While the original nucleus accommodates mainly the upper middle class and politicians, by far the greater portion of the population, covering a wider social range, lives in the 27 surrounding satellite towns.” Those satellite towns, akin to Brazil’s favelas, were not intended to be part of Costa’s final concept, but they developed organically to hold the Plano Pilato’s overflow, and today they highlight the socioeconomic disparity that troubles many major cities around the world, and especially those in Brazil.

Yet there’s still a sense of pride in the capital city. “If you speak with residents of Brasília, they immediately will tell you how much they love their city and that they would never move to any other Brazilian city,” says Dr. Lehmann. And it’s important to recognize the city’s successes, too, namely in the progressive ideals of the concept, the monumental and now iconic architecture, and the remarkable speed at which the development was completed.

“When I think about Brasília, I’m still in disbelief regarding the ability to realize a dream of such scale and ambition, which is totally unprecedented,” says Boston-based architect Amir Kripper, who was born in Brazil. “At the same time, it makes me hopeful that with the right political environment, a brighter future is possible and achievable.”